The day is now Thursday, July 2, and we are going to see one of the greatest museums on earth: the British Museum. It is a museum that rivals (if not surpasses) the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. and is utterly remarkable due to its outrageously vast collection of ancient and rare artifacts. But first we are going to see a section of the museum which most visitors never glimpse: the archives.

One might assume that the archives of such a massive and prestigious institution as the British Museum must be extensive and extremely well looked-after. This is not necessarily the case. See, the British Museum is an artifact-centered institution. That is, most of its focus is on the preservation and display of artifacts, not documents. And since archives deal mainly with documents, the archives of the British Museum are woefully underserved.

That is not to say that they are completely neglected. Francesca, the sole archivist, does a fantastic job with what she is given. She has to handle the museum’s records, which date back to before the 1740s (the earliest being a will from 1738), almost by herself, with only some help from interns and people in other departments. However, it is interesting to see the disparity between the grandiosity of the museum itself and the relative insignificance of the archives.

Which is quite a shame, because the archives contain some utterly fascinating documents. For example, the archives contain officers’ records from 1805 to 1869, which explain how many of the items in the museum were acquired. These can yield some fascinating stories, although they are hardly comprehensive. Many of the items in the museum were acquired in secret so their origins are not known, and even some of the items with records are not complete.

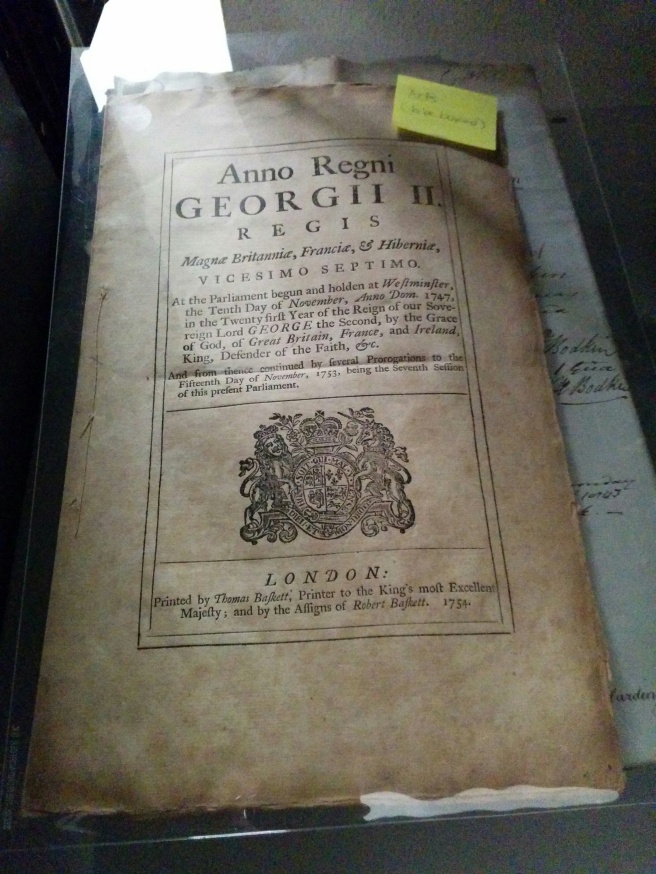

Other items of note in the archives include lists of establishment, which list all library staff members and their salaries dating from the early 1900s; acts of Parliament, the earliest dating to 1747; letters from Lawrence of Arabia, which are bound as part of a record of excavation in Syria; and photographs of the museum throughout its history, the earliest being a photograph of the reading room from 1855.

Although the archives seem to be a bit neglected overall, things are hopefully trending in the right direction. Items are now in the process of being cataloged and hopefully digitization is not too far behind. The archives receive 2,000 inquiries per year so it is not as if they are insignificant. I will look forward to seeing how the archives evolve over the years to come and become a more significant and visible part of the British Museum.

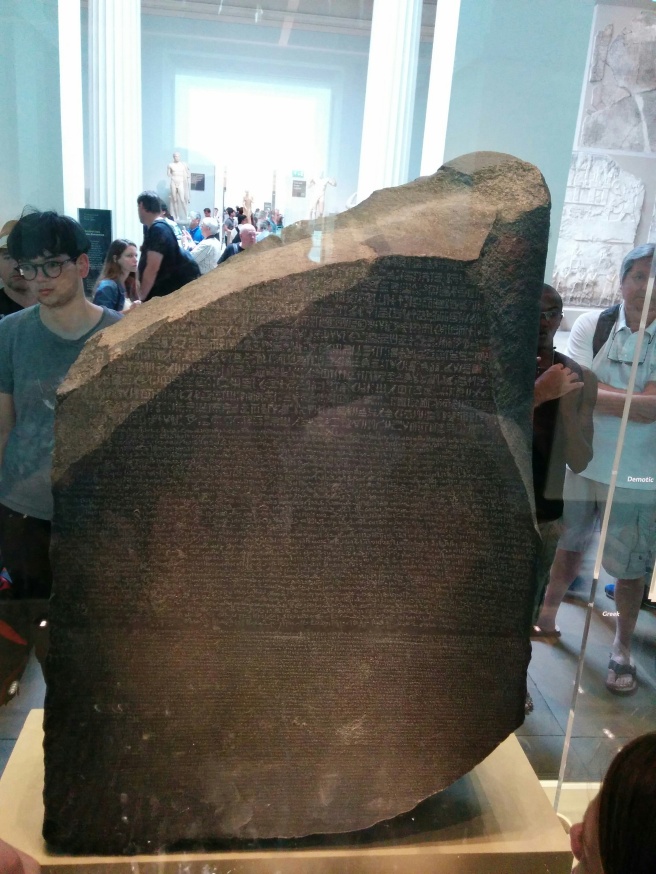

The museum itself was fantastic, although unfortunately we did not get to tour it for very long. Even so, the amount of stuff we saw in a short period of time deserves its own post, so I will hold off on including it here. But just as a taste of what is on hand at the museum, here’s a picture of the actual Rosetta Stone:

As if seeing one of the greatest museums in the world wasn’t enough, we had another stop on our list for the afternoon: the Royal Geographical Society. This is a bit of a hidden gem which most visitors will probably overlook. It’s located right next to the Royal Albert Hall in a rather unassuming little building, but it holds a number of fantastic treasures of massive historical significance. Unfortunately we were not permitted to take pictures of the artifacts, but what the society had on hand was incredible.

The Royal Geographical Society was founded in 1830 in order to promote “scientific geography” (that is, exploring). Having read a book on David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley, I was particularly interested in artifacts relating to Livingstone’s expedition to find the source of the Nile and Stanley’s search for Livingstone. I was not disappointed, as the Society had Livingstone’s compass, a pair of Stanley’s shoes, and (most impressively) Stanley’s hat among its artifacts. The Society has over 2 million items, including 1 million maps, a half million images, 250,000 books, 500 boxes of archival materials, and 1500 objects and artifacts. Other interesting items which we got to see included an Inuit snow visor, biscuits and chocolate from old expeditions, Ernest Shackleton’s helmet and bible, and Roald Amundsen’s eyepiece. Although the artifacts are just a small part of the Society’s collection, they are some of the most fascinating pieces and were a treat to see.

Lest you think the Royal Geographical Society is just a place for preservation and history, know that it is still extremely active. The Society still awards grants and supports explorations. The reading room, which opened in 2004, consolidated four separate rooms and provided a better space for external researchers. An online catalog was also created, which increased the range of visitors to the Society. Far from being just a museum and repository of the past, the Royal Geographical Society is alive and well and certainly worth a visit.

Hey, looks like fun!

LikeLike